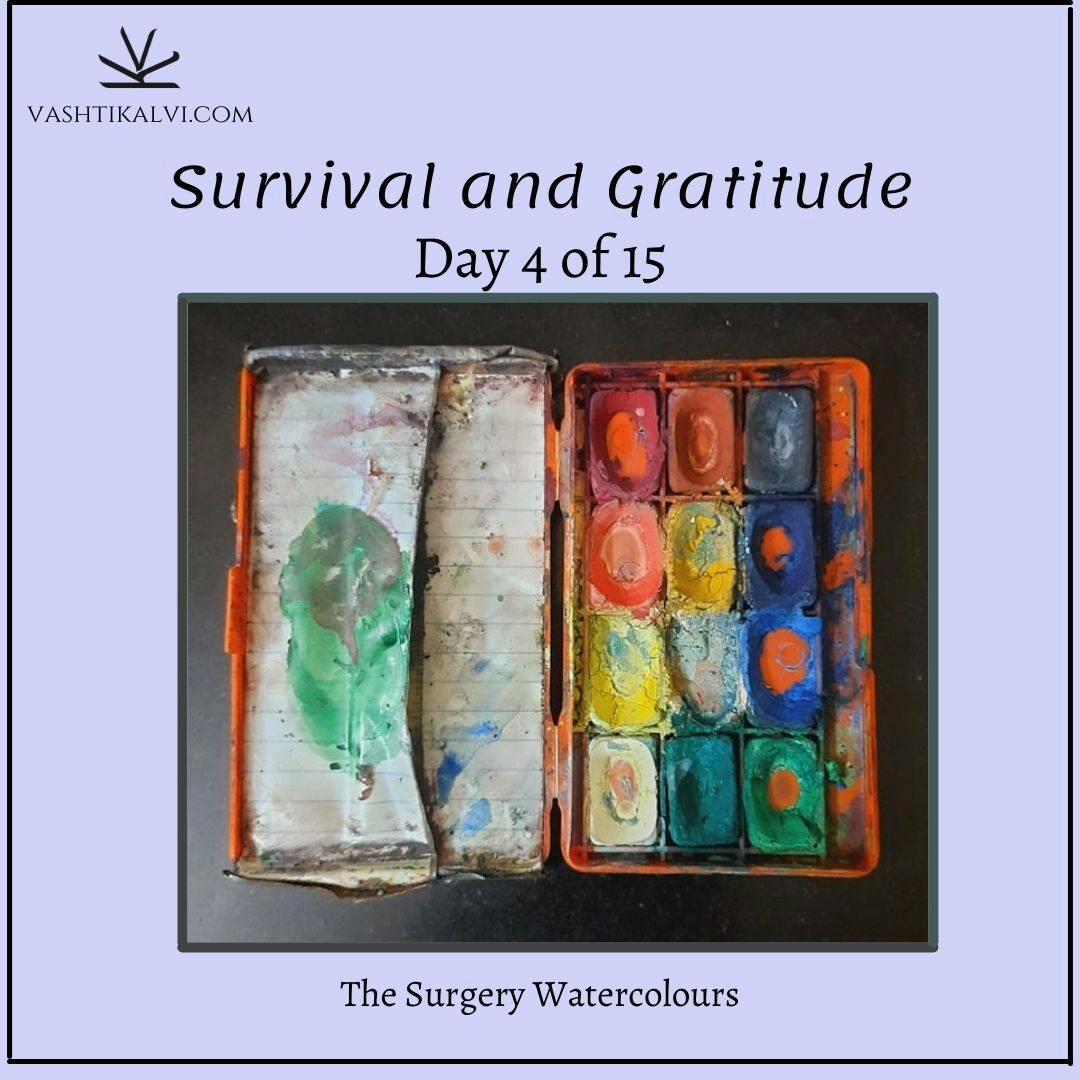

This is the set of water colours I’ve been using for the last two years. Until I tried to photograph it for this post, I had forgotten that it cost me 30 Ruppees. In 2019. And it’s still going strong, so I can’t buy a new set. I acknowledge the audacity that is complaining about it. As awful as the paint is, the whole box fits into my palm, and it has been on some real journeys with me. The night before surgery, after I’d begrudgingly bought it for want of anything else, I predictably got up to some arts and crafts nonsense.

I fit paper into a ziploc bag with the zip cut off. I taped it shut with cellotape, and attached that to the inside of the lid. At the time, my watercolour technique used hand sanitizer instead of water. This was pre-pandemic, but it wasn’t any less fatted then. The principle of using alcohol instead of water is great though. It means paint strokes can be a lot more pigmented, paint dries faster, and you can clean the brush just by wiping it dry with tissue.

My paper-in-a-plastic-bag palette only worked because of the sanitizer technique, so I took it up a notch and made a fold, so there’d be more surface area for me to mix colours on. And then I taped the fold into a pocket, so that the unevaporated alcohol had somewhere to gather. Then I lined the pocket with medical tape for absorption.

Everyone in the hospital called it micropore. It’s relatively gentle on hair when it needs to be taken off, it’s easy to tear with your fingers, and can handle some moisture without becoming instantly useless. “This damn hospital is held together by micropore” someone said, in one of many, many moments of frustration.

Like I’ve said, I’m grateful, I swear. My doctors and surgeons were amazing. We had family and friends who had been doctors in the hospital, and we had a lot of help with the bureaucracy. Most frustrating moments were the fault of my body not doing what it was supposed to. But there were definitely moments when it was the hospital’s fault.

The first big incident was before my first cancer surgery. The tumour was the size of a football, and I looked pregnant. From what I understand of pregnancy, I felt pregnant too. The surgery was scheduled for a week later, and I was in pain, so I’d been asked to get admitted. I’d been in bed, in pyjama shorts and a tee-shirt, when the pain began, and that’s how I showed up at the ward. I was alone. And the nurses wouldn’t admit me.

“Go change your clothes.” I was told. At first, I was too baffled to protest, but I also didn’t have a change of clothes. “Then go buy them. There are many shops on this road.” It took three hours for them to give me a bed. The gist of it was that my clothes were too revealing. I don’t think I would have got the bed at all if it wasn’t for personal connections with people in the hospital.

I imagine I was livid, but I know I was too exhausted to do anything substantial about it. I sat with my father one night that week, and we tried drafting a letter of complaint. I had an impending surgery, and an unconfirmed but strongly suspected cancer diagnosis. We didn’t get very far.

A few weeks later, after the surgery, and the chemotherapy recommendation, I was packing for the hospital. I found this skin-tight mini skirt I used to love wearing in college. I’d stopped wearing it because my stomach had become too big. I’ll never know if it was just regular weight, or the tumour. Whichever one, it’ll always be sad that that’s why I stopped wearing the skirt. It still fit, it just looked like I had a stomach.

Today, I’m grateful for pettiness. My brother made a joke about showing up for the first session in the skirt, and I took it to heart. I carefully chose the strappiest, most skimpy clothes I had. The less appropriate they seemed for a hospital, the better. Any neckline that covered my collar bones was too high.

I had this bitter hope that someone would say or do something nasty, just so I could bite back. No one ever did. By that point, I was too much of a patient, so I was never alone without someone I could trust. I was never without someone who would fight for me. And I used that assurance to wear long tops as dresses on the way to have drugs pumped into my shriveling veins for six hours a day.

Every single time, as soon as I was admitted, I changed into hospital robes. For intensive treatment, like chemotherapy, it's highly recommended. In case there’s an emergency surgery that needs to happen, if you aren’t wearing a hospital robe, they’ll have to cut you out of the clothes you’re wearing. I was not about to risk that.