When you’re going in for surgery, they have you take off your jewellery. It’s a safety issue, I was told. It made sense to me that necklaces and bracelets would need to be removed, dangly earrings even. I didn’t want to remove my nose rings, but apparently, the cauterizing machine could spark against the metal and cause burns. I remember counting all the pieces of jewellery: two nose rings, two toe rings, three finger rings, and eleven earrings.

After the first surgery, I was able to put the jewellery back on within a few days. My cousin and mother decided that it was time to put my jewellery back on, so I could feel more like myself. At the time, I didn't have the energy to disagree, so I went with it. When I went to the bathroom, I vaguely hoped that I’d have an easier time looking in the mirror, but I didn’t. My face felt more like mine, yes, but it didn’t matter. I couldn’t even stand up straight because my abs had recently been sliced open down the middle.

Two days after the surgery, a doctor had ripped off the bandage, and I saw the thick black sutures curving around my belly button. I felt nauseous with disgust. Eventually, when the scar healed, it wasn’t so bad. It framed my belly button neatly, and I wrote poems about it.

The two surgeries that I had later, along the same incision line, compounded over the first scar. My belly button is now off-center, and barely there. There are now scars from two sets of sutures, and another set of staples. It’s less visceral now, but I have only ever been able to describe it as grotesque. In many ways, adolescence felt like a process of learning to look in the mirror and like what I saw. After I’d finally got there, it hurt to lose it to something that was, technically, helping me heal.

I feel like I remember the moment that I became self conscious about my appearance as a child. I’d been looking at myself in the mirror on my mother’s closet, and some adult - one of my parents, maybe an aunt- asked if I thought I looked beautiful. I must have said yes, because then they asked what I thought was beautiful about me, and I remember being floored.

Somehow that question knocked me into this spiral of self awareness- not everyone saw me the way I saw myself, I wasn’t necessarily actually beautiful, I needed to look a certain way to be beautiful. With cancer, the surgeries, and my irrevocably destroyed belly button, looking in the mirror was a reminder that even if I managed to be beautiful, it could be taken away. It was the most concrete way that I saw how disconnected I felt from my body.

When he was 10 months old, my parents had a mirror made for my baby brother’s physiotherapy and occupational therapy. He had Down’s Syndrome, and needed help with developing movements, like walking, and gripping. They were told it was important for him to be able to see himself while he did the exercises. The mirror was made big enough so that someone could sit with him, holding his hand through gestures like stringing beads, and they could both see themselves and each other in the mirror.

I thought about that a lot after my surgeries, when I needed two people to help me to the bathroom and back, when I was made to practise walking with an attendant, and when I was finally able to walk on my own again. I thought about it during depressive episodes when I was looking in the mirror to put on eyeliner, or contact lenses, and couldn’t really recognize myself. I knew, obviously, that I was looking at myself in the mirror, but it didn’t feel real.

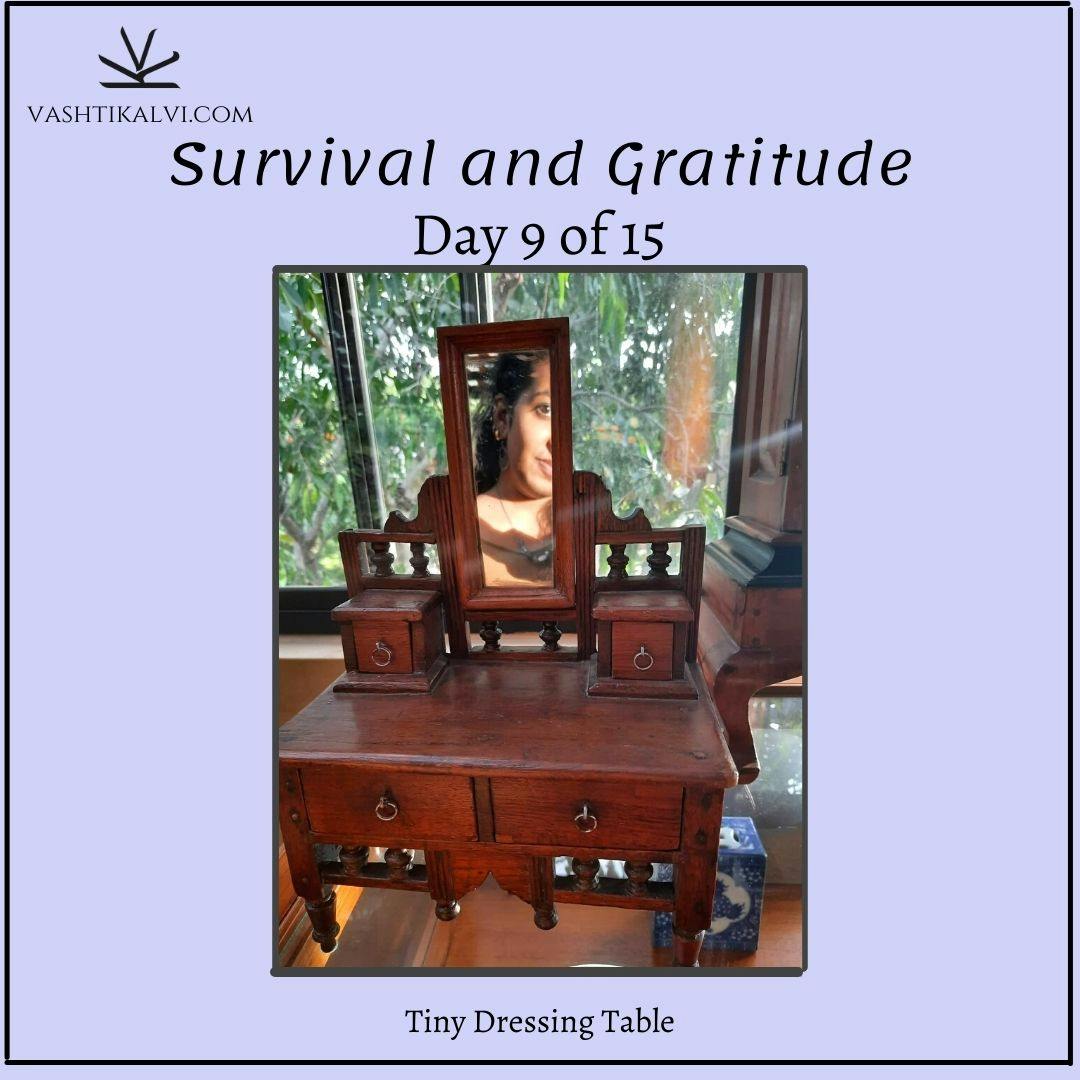

Today I’m grateful for mirrors. Not too long after the first surgery, I’d become painfully uncomfortable in my body. It was like going through puberty again. I’d become severely touch-averse, and it didn’t help that I was constantly aware of how I needed to exercise.

I started taking salsa lessons, in a dance studio with a mirror that spans the wall. I slowly got better at letting people touch me, even though that went a bit awry with the pandemic. I hadn’t anticipated how difficult it would be to make eye contact with my reflection, but it was so wonderful when I finally could. I learned to watch myself in the mirror as an act of self-improvement rather than criticism- to fix my posture, fix my expressions, to make sure I’m exercising correctly. With everything happening around me, and to me, I don’t know how I would get by without being able to see my body, and how it occupies the space around me, so I can remember how to see myself as a person.